This post is the follow-up of the Motors-in-robotics series. Although what I will present you here is still basic notions and can be addressed to anyone keen on knowing more about it, don't hesitate to have a look at the previous posts (types of motors in robotics, DC motor direction, and speed control, how to read a datasheet), they will help you expand your knowledge about electric motors and start on a reasonable basis.

Your DC brushed motor is full of surprises: you think feeding it with some electric power kindly provides a turning shaft. Sometimes it spins fast, sometimes slower, and with more or less force — actually torque —. That's something unique, and that's good enough.

But that's not quite everything.

Remember this image I put in one of the first posts about motors?

It's highly simplified, though, and reality is slightly different.

What I will detail here is still simplified but a little more precise.

A motor generates more than a rotation, more than only torque and speed. Many other things are getting out of it, and they go from something you don't care about to things you wish never existed. Let's review everything that really comes out of your motors.

Torque and speed

We begin with the basics. Both these outputs are the most important because they are the ones we want. A motor is supposed to rotate. It rotates, cool, now let's have a coffee.

What are they? Torque is the force applied at a distance to an object's pivot —hence it's a Force time a Distance —, allowing the object to rotate. The International System of Units measure is represented in Newton-meter (N.m) (1). Applied to your motor, torque is also the rotational force provided by the rotor.

Speed is the rotational speed of the rotor. Nothing much to say about it, because you already know from a previous post that you can control that speed with easy electronics and PWM. You can express it in radians per second (rad/s), or most of the time, in revolutions per minute (rpm) (1).

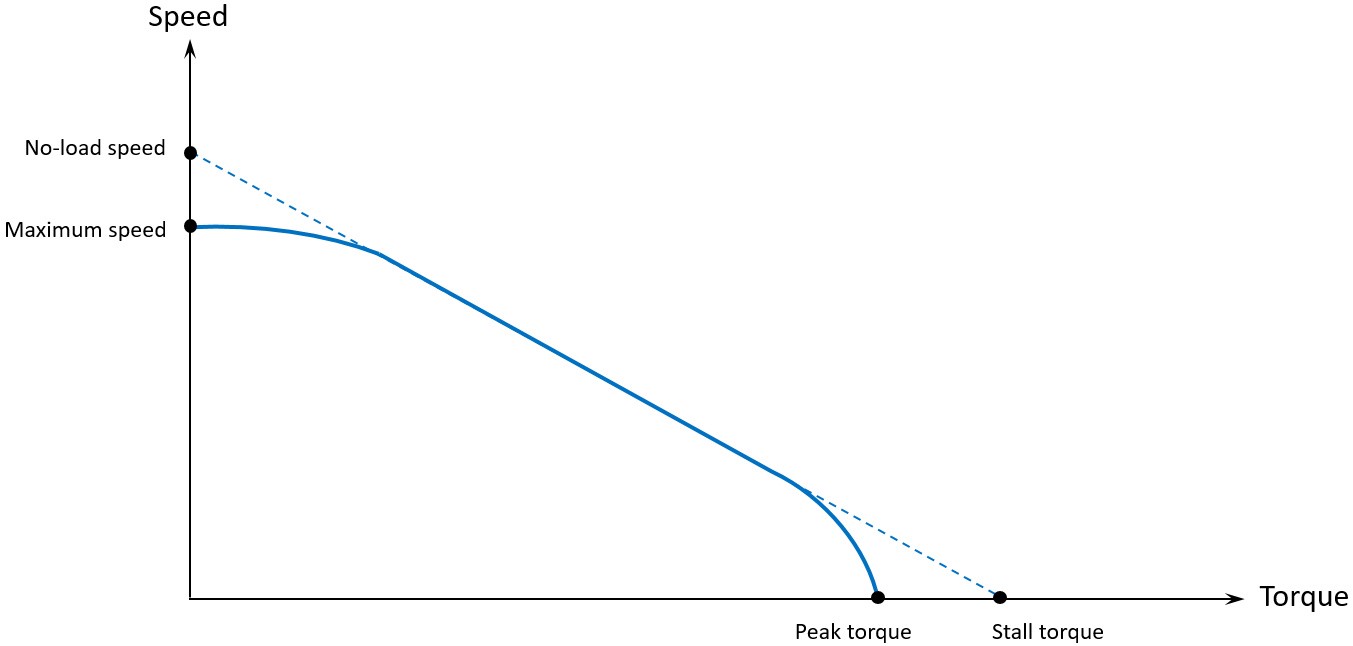

Let me remind you that in a DC motor, high speed means low torque and inversely. On the characteristic curve, it looks like this:

The following function represents this curve:

We already discussed this in a previous post, but it's attractive to be precise that this linear curve is theoretical. In your real world, it may look like that:

Moment of inertia

Because while a motor is working, its rotor is a spinning mass. And any rotating mass has a moment of inertia. You can see it as a factor to calculate how much torque is needed to give a movement to an object. Its unit is kg.m² (SI), or lb.ft².

The moment of inertia — also called rotational inertia — of an object depends on three factors:

- The object's mass

- The position of its axis of rotation

- Its mass distribution around this axis

For example, more torque is needed to rotate to a free horizontal bicycle wheel than to rotate a small rotor. Both masses are evenly distributed, but the bicycle wheel is heavier, and some of its group is far away from the axis of rotation; for the rotor, it's light, and the mass is very close to its axis of rotation.

To ease the painful life of science people, the moment of inertia calculation can be simplified or assimilated to a reference solid (like a sphere, a cube, etc.).

Angular acceleration

DC motors need to provide acceleration to change speed. For example, from idle speed to whatever speed a rotor wants to get, the transition is not spontaneous (because an infinite acceleration, as well as a null moment of inertia, are strongly unlikely). It needs an acceleration to reach a given speed. In the case of reducing the speed, a deceleration is only negative acceleration.

Acceleration — actually angular acceleration —, torque, and moment of inertia are closely linked together by this equation:

Torque (T) (in N.m) is equal to moment of inertia (I) (in kg.m²) times angular acceleration (alpha) (in m/s², all the units here are form SI). This equation appears in Newton's law of motion.

Back electromotive force

Also called counter electromotive force, back-EMF, or CEMF. Back-EMF is a voltage (in V), a difference of potential. In the coils of a motor, it appears while electrons are moving through the wires while under a motion of magnetic field (Lenz's law) may explain it better than me).

This one is tricky because electromotive force and back electromotive force are the same phenomena. Only one of them (back-EMF) exerts a mechanical force opposing the motion of the motor, while the other is giving a rotation to the motor (you already know the process, by the way).

A back-EMF can be measured by a voltage generated at the output of the motor, which, in certain cases, can damage the electronic circuits.

However, back-EMF is proportional to the rotational speed of the rotor, making it sometimes very useful to measure them.

Did you know that Luos connects every part and function of your electronic devices into a single system image?

Heat

Heat is a recurrent encounter when dealing with electrical power. Why is that? It's because electrical power is always put face-to-face with electric components, and many of them have more or less resistance to electricity. This resistance means electrical power is transformed into heat. A famous equation calledJoule's first law explains it:

In this equation, R is the resistance of any conductive component, and i is the current which flows through this component. Pth is the thermal power, _i.e., the power (2), which is transformed in pure heat emitted from the component.

In a DC brushed motor, electricity flows into the winding; having a resistance, this winding tends to heat according to the amount of current.

To summarize:

A part of electrical power is continually transformed in heat if passing through electric components.

By the way, more a component (like a motor) tends to heat, the more its efficiency — which is the ratio of output power by input power— is said to below. High-efficiency components will emit very little heat.

Also, while running, a DC brushed motor has constant inside friction between brushes and commutators and between shaft and housing through plain- or ball-bearings. This friction is a heat generator as well, i.e., an efficiency-killer.

This was the third thing that comes out of a motor, and wait here. There is more.

Magnetic field

Of course, you remember this one from a guide to motors in robotics. Most electric motors run with a magnetic field — not black magic.

The electricity runs through the winding, generating a magnetic field and motioning electrically-induced or permanent magnets. One sentence to summarize how a motor works! Sweet.

Let's precise that only the permanent magnets produce a "static" magnetic field. The rest, particularly the magnetic field from the winding, is more likely to be called electromagnetic. We will see that in a short while.

Anyway, all this magnetic mess is not disappearing away. It forms imaginary lines from one pole to another (negative to positive), which we call a magnetic field, all around the motor. Its strength is measured in Amperes per meter (A/m). The representation of lines, though imaginary, is an excellent model to help to understand how a magnetic field would look if you had superpowers.

The Earth happens to have something similar:

Any magnetic material (e.g., an iron-made object) put near a motor will interact with its magnetic field. Although no material can stop and cancel a magnetic field, it's possible to create shields that can redirect the magnetic lines.

EMI

So now who even is this Emi, and what does she have to tell us about motors?

EMI stands for Electromagnetic Interference. It's a blend of electronic and magnetic fields, both perpendicular to each other and their propagation direction.

To simplify, we can say it's a radiation of energy through the air around the motor. It's caused by the electricity running through winding and commutators, brushes, terminals, and wires.

These kinds of interference are not really welcomed, if not unwanted. They can highly affect electronic circuits to go as far as stopping working. Fortunately, electromagnetic shields can be applied to reduce their propagation.

Note: Communication buses used to send a signal—eg. I2C — can be sensitive to interference. However, some of them provide differential pair, which is the same signal transiting on two wires of the same length, one signal being opposed from the other one. The electromagnetic interference being the same on both wires, the difference of signal at reception allows getting a clean signal. This is why the bus associated called Robus (from Luos Robotics) uses a differential pair.

Following your reading and new knowledge on motors, don't hesitate to follow our Get Started tutorial to continue training step by step:

Bonus: Noise, vibrations, light, and other stuff

Noise

There is not much to say about noise: only it's generated mostly from the friction of brushes on commutators and shaft on bearings. Also, some vibrations can appear on the shaft at high speed and increase the noise.

The electrical signal frequency through the winding may sometimes generate noise, particularly between 100 Hz and 8000 Hz (more or less the audible range of human hear). Controlling motors at 20 kHz is a way to avoid high-pitched noises.

Vibrations

Motorization implies motion, and even though the rotor's axis of rotation is fairly situated at its center of mass, the inertia is never perfectly balanced. Every motor generates more or fewer vibrations.

“Light”

Technically, heat generation implies photon generation, i.e., light. But this would be quibbling to say that the winding could heat at the point to generate visible light and that the light would be visible through the interstices of the motor's housing, not to mention this would imply the motor to be melting and… burning, so not working anymore. But, technically, yes, "light."

Smell?

Talking about quibbling, ever try to smell a running motor? The kind of plastic shield around the coils' wire could emit some smelly particles while heating.

I think it's time to stop here. Please don't even try to taste a motor.